Aquila (Roman)

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2025) |

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Military of ancient Rome |

|---|

|

|

An aquila (Classical Latin: [ˈakᶣɪla]; lit. 'eagle') was a prominent symbol used in ancient Rome, especially as the standard of a Roman legion. A legionary known as an aquilifer, the "eagle-bearer", carried this standard. Each legion carried one eagle.

The eagle had quasi-religious importance to the Roman soldier, far beyond being merely a symbol of his legion. To lose a standard was seen as extremely grave, shameful and dishonorable, and the Roman military went to great lengths both to protect a standard and to recover one had it been lost; after the annihilation of three legions in the Teutoburg Forest, the Romans spent decades retaliating for the defeat while also attempting to recover the three lost eagles.

No legionary eagle standards are known to have survived. However, other Roman eagles, either symbolizing imperial rule or used as funerary emblems, have been discovered.[1]

History

[edit]The signa militaria were the Roman military ensigns or standards.[2] The most ancient standard employed by the Romans is said to have been a handful (manipulus) of straw fixed to the top of a spear or pole. Hence the company of soldiers belonging to it was called a maniple. The bundle of hay or fern was soon succeeded by the figures of animals, of which Pliny the Elder (H.N. x.16) enumerates five: the eagle, the wolf, the ox with the man's head, the horse, and the boar.[3][4] Pliny attributes to the consul Gaius Marius the setting aside of the four quadrupeds as standards and the retention of the eagle (Aquila) alone after the devastating Roman defeat at the Battle of Arausio against the Cimbri and Teutons in 104 BC. It was made of silver, or bronze, with upwards stretched wings, but was probably of relatively small size, since a standard-bearer (signifer) under Augustus is said in circumstances of danger (the Teutoburgerwald battle) to have wrenched the eagle from its staff and concealed it in the folds of his tunic above his girdle.[5] Pliny's claim is refuted by sources showing late republican and early imperial legions with other animal symbols such as bulls and wolves.[6]

Even after the adoption of Christianity as the Roman Empire's religion; the eagle continued to be used as a symbol by the Holy Roman Empire and the early Byzantine Empire although far more rarely and with a different meaning. In particular the double-headed eagle, despite strongly linking back to a Pagan symbol, became very popular among Christians.

Lost aquilae

[edit]- Battles where the Aquilae were lost, units that lost the Aquilae and the fate of the Aquilae:

- 73–71 BC – five Aquilae were lost over the course of the Third Servile War, recovered upon the defeat of Spartacus in 71 BC.[7]

- 53 BC – the defeat of Marcus Licinius Crassus at the Battle of Carrhae by the Parthians. Several Legions (returned in 20 BC).

- 49–45 BC – loss of Aquilae from legions of Aulus Gabinius and Publius Vatinius to the Dalmatians during Caesar's Civil War.[8] (returned in 23 BC).

- 45 BC – loss of Aquilae in Spain during Caesar's Civil War.[8] (returned in about 25 BC during the Cantabrian Wars).

- 40 BC – defeat of Decidius Saxa by a combined Roman–Parthian force under Quintus Labienus near Antioch.[9] Several Legions (at least one Aquila was returned in 20 BC).

- 36 BC – the defeat of Oppius Statianus by the Parthians during Antony's Parthian War. Two Legions (returned in 20 BC).

- (19 BC – degradation of a legion during the Cantabrian Wars by removal of the name "Augustan Legion".[10] The actual reason is unknown)

- 17 BC – defeat of Marcus Lollius by Germanic tribes in Gallia in the Clades Lolliana. Legio V Macedonica[11] (returned in 16 BC)

- 9 – Battle of the Teutoburg Forest in Germania. Legio XVII, Legio XVIII, and Legio XIX (two recaptured by Germanicus in 15[12] and 16,[13] the last recaptured by Publius Gabinius Secundus in 41[14]).

- 66 – First Jewish–Roman War. Legio XII Fulminata (fate uncertain).

- 70 – destruction of Legio XV Primigenia during the Revolt of the Batavi near Xanten. (fate unknown)

- 86 – defeat of Cornelius Fuscus in the First Battle of Tapae during Domitian's Dacian War.[15] Legio V Alaudae or Praetorian Guard (recaptured during Trajan's Dacian Wars in 101 or 102[16]).

- (132 – disputed loss of Legio XXII Deiotariana or Legio IX Hispana in the Bar Kochva Revolt[17])

- 161 – defeat of Marcus Sedatius Severianus by the Parthians at Elegeia in Armenia.[18] Possibly the Legio IX Hispana or Legio XXII Deiotariana.[19]

Arch of Constantine

[edit]Arch of Constantine showing carvings of aquila

Ancient imagery

[edit]-

Emblem of the 20th Legion on a roof tile

-

Memorial to Lucius Duccius Rufinus, a standard-bearer of the Ninth Legion, Yorkshire Museum, York

-

Detail of the central breastplate relief on the statue of Augustus of Prima Porta shows the return of the Aquilae lost to the Parthians. The return of the eagles was one of Augustus's notable diplomatic achievements.

-

The Praetorians Relief showing an aquila from the destroyed Arch of Claudius in Rome.

-

Detail from the Arch of Constantine in Rome

-

"The Reliefs of Trajan's Column by Conrad Cichorius. Plate number LXXII: Arrival of Roman troops (Scene XCVIII); The emperor sacrifices by the Danube (Scene XCIX); Trajan receives foreign embassies" (Aquila at the upper left)

-

Aureus minted in 193 by Septimius Severus, to celebrate XIIII Gemina Martia Victrix, the legion that proclaimed him emperor

-

Roman Coin showing the aquila in the Temple of Mars the Avenger in Rome

-

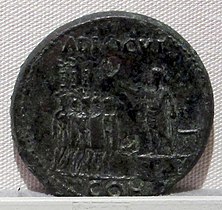

Coin showing Germanicus holding an Aquila

-

Coin of Emperor Caligula showing several Aquilae at the left.

-

Sestertius minted in 248 by Philip the Arab to celebrate the province of Dacia and its legions, V Macedonica and XIII Gemina. Note the eagle and lion, symbols on the reverse, respectively of legio V and legio XIII.

See also

[edit]- Silchester eagle

- French Imperial Eagle, a revival of Roman practice in the Napoleonic army

References

[edit]- ^ "Roman eagle found by archaeologists in City of London". The Guardian. 2013-10-29. Archived from the original on 2023-06-26.

- ^ Yates, James, "Signa Militaria" in Smith, William, A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities, John Murray, London, 1875, pp. 1044–1046 (http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/secondary/SMIGRA*/Signa_Militaria.html)

- ^ The ox is sometimes confusingly described as a Minotaur. See Festus, s.v. Minotaur.

- ^ Theodore Mommsen, History of Rome, vol. 3, p. 459.

- ^ Florus Epitome, book II XXX,38

- ^ Taylor, Michael J (2019). "Tactical reform in the late Roman republic: the view from Italy". Historia. 68 (1): 79 n. 14. doi:10.25162/historia-2019-0004. ISSN 0018-2311. S2CID 165437350.

- ^ Frontinus Stratagems 2.5.34

- ^ a b Res Gestae Divi Augusti, 29

- ^ Cassius Dio 47, 35–36

- ^ Cassius Dio, 54.11

- ^ Velleius Paterculus, Vell. II – 97

- ^ Tacitus Annales 1, 60

- ^ Tacitus, ann. 2,25

- ^ Cassius Dio 60,8,7

- ^ Tacitus, De vita et moribus Iulii Agricolae, 41.

- ^ Dion Cassius, Histoire romaine, livre LXVIII, 9, 3.

- ^ Peter Schäfer (2003) The Bar Kokhba War Reconsidered: New Perspectives on the Second Jewish Revolt Against Rome Mohr Siebeck ISBN 3-16-148076-7 p 118

- ^ Cassius Dio LXXI.2

- ^ Duncan B Campbell, The fate of the Ninth: The curious disappearance of Legio VIIII Hispana", Ancient Warfare

Further reading

[edit]- Signa Militaria", by James Yates, in the public domain A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (pp. 1044–1046)

- Kai M. Töpfer: Signa Militaria. Die römischen Feldzeichen in Republik und Prinzipat, Mainz, Verlag Schnell + Steiner 2011, ISBN 978-3-7954-2477-0

- The Eagle of the Ninth, a novel by Rosemary Sutcliff